Films about Rotterdam - From Port City to Film Set

Share

Rotterdam is impossible to film

The images changed too quickly

Rotterdam has no past

and not a single stepped gable

Rotterdam is not romantic

has no time for nonsense

is not susceptible to suggestions

doesn't listen to idle talk

It's not camera sensitive

doesn't look better than it is

It lies square, high and angular

tilted in the backlight

Rotterdam is not an illusion

woken up by the camera

Rotterdam is impossible to film

Rotterdam is way too real

Jules Deelder, Rotown Magic, 2004.

1 Hollywood on the Maas

'Rotterdam is niet te filmen' (Rotterdam is not to be filmed), is the first line in the poem Rotown Magic by Rotterdam poet Jules Deelder. The poet manages to capture the image of the city in a few key words, in which he aptly expresses the historical background, mentality and characteristic cityscape of Rotterdam. Rotterdam and film have grown ever closer in recent years. In a period of two decades, the port city has grown into a true film city of the Netherlands. Every day, image makers use the Rotterdam surroundings as a backdrop in feature films, documentaries, commercials, television programmes, video clips and art projects. Although the city has been captured in thousands of works since the dawn of cinema, it received a new impetus in the 1990s with the international kung fu film Who am I (Wo shi she; Jackie Chan, 1998). Who am I was shot at a large number of locations in Rotterdam and shows many of the city's iconic images. For the first time, the Rotterdam skyline appeared in a spectacular way as a backdrop in an international blockbuster. Chan's film put Rotterdam's cityscape on the map and soon advertisers and filmmakers began to capture the cityscape on film more than ever before.

Another cause of the revival of film in Rotterdam was the arrival of the Rotterdam Film Fund (RFF), which was established in 1996 on the initiative of the municipal government. The fund provided interest-free loans to filmmakers and producers, and as a result, the audiovisual culture in the city received a new impulse. More and more filmmakers and media companies settled in Rotterdam and the city was nicknamed 'Hollywood on the Maas'. The initiative paid off and is responsible for a large number of film productions. An important criterion of the fund was that a film production had to contribute to the image of Rotterdam. This criterion was set at the request of the municipality and is in line with the fact that Rotterdam pays a lot of attention to its image. But what is this image and how does film contribute to the image of the city?

1.2 Manhattan on the Maas

Nowadays, cities compete with each other on a national and international level and media are an indispensable part of our society. A city is strongly dependent on its image in attracting residents, visitors and companies. Rotterdam, like no other Dutch city, pays attention to its image via media. The image of the city now takes many forms. During the past century, Rotterdam's image has changed several times as a result of radical transformations in the field of urban and industrial developments. Paul van de Laar states in Stad vanformaat (2000) that Rotterdam changed from a port city or transit city to a modernist working city after the Second World War. Subsequently, the emphasis on the expansion of port activities and trade was put aside in order to profile Rotterdam as a cultural city from the end of the 20th century, in order to compete with the cultural cities of Amsterdam and The Hague. In addition, it distanced itself from modernist ideas in the field of urban development and the cityscape underwent large-scale renewal, accompanied by special architecture and a wave of high-rise projects. Patricia van Ulzen writes in her follow-up study to Van de Laar's, Dromen van een metropool: de creatieve klas van Rotterdam 1970-2000 (2007), that Rotterdam has acquired the image of a metropolis since the 1970s. According to Van Ulzen, this image was created by a group of people from the creative sector, called the 'creative class' by her, who, since the 1970s, provided a metropolitan vision of the city with all kinds of urban initiatives (p. 38). She describes the prevailing image of the city, which has emerged thanks to these initiatives and urban developments, as follows:

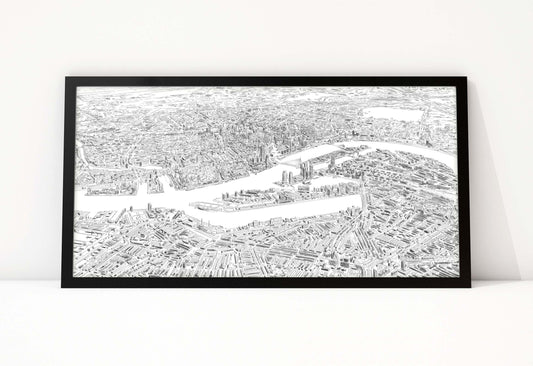

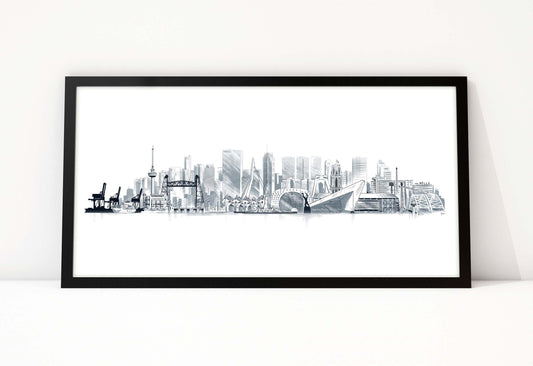

The term world city sticks to Rotterdam, as do the derivatives of that term: international city, world port city, modern city, real city, vibrant city, cosmopolitan city. Rotterdam seems like a large world city when the skyline on the banks of the river Maas is pictured, with tall, modern buildings that evoke the words 'Manhattan on the Maas' (Van Ulzen 2007: p. 8).

Furthermore, Van Ulzen states that the image of Rotterdam has specific nuances that other metropolises do not have. For example, the city was characterized with descriptions such as 'work ethic' and 'decisiveness'.

But despite all these positive associations, Rotterdam struggles with a negative image. The traditional port and working city had a poor appeal to middle-class and highly educated residents, who therefore moved en masse to the suburbs. The less educated residents were left behind, with the result that Rotterdam became a record holder in the 'leading of bad lists' when it comes to unemployment, benefits, school drop-out, crime, etc. Van Ulzen quotes a New Year's speech by mayor Ivo Opstelten from 3 January 2000, in which he describes the dark side of the city: 'But, I can see you thinking: what about safety, the vulnerable groups in our society, unemployment, poverty. Isn't Rotterdam the city that heads the wrong lists? You are right: another image of Rotterdam is that our city shares more than its fair share in the problems of the metropolitan area' (p. 25).

Rotterdam also wants to try to attract and retain more middle-class and highly educated residents to the city. Rotterdam does this on the one hand by building more expensive housing, improving the public space and creating more cultural facilities. In addition, the municipality has started to portray Rotterdam as a yuppie and cosmopolitan city by means of large-scale promotional campaigns since 2004. The largest campaign was the so-called 'Rotterdam Durft' campaign, carried out by the OntwikkelingsBedrijf Rotterdam. With this campaign, the municipality wanted to make it clear that Rotterdam is not a raw port city with only problems, but also a city where people can live, work, study and relax pleasantly. The campaign was accompanied by a large number of promotional films for the city itself, for festivals and for sporting events. With these films, Rotterdam made an attempt to change the existing image. Rotterdam is trying to solve its image problem through film.

Film can have a great influence on the image of a city. For example, major world cities such as New York, Los Angeles and London are portrayed as crime cities in films and television series. The metropolitan problems such as crime and social unrest are magnified in these media. The streets of New York are used remarkably often in crime films and police series. London has traditionally been portrayed as the city of serial killers, partly thanks to film (Ulzen, 2007: p. 25). According to Van Ulzen: '[...] the image of the city can at a certain moment direct the urban development, but vice versa, urban development influences the image' (p. 34). Because many films use the urban environment as a backdrop, the medium also influences the image of the city that is depicted. In the same way, film productions that use Rotterdam as locations influence the image of the city.

Constructing the image of Rotterdam through film is exactly what the city council had in mind when establishing the Rotterdam Film Fund. The initiative to influence the image of Rotterdam through film can have two effects. Film can create both a negative and a positive image of the city. However, the Rotterdam city council recently decided to abolish the film fund in the context of large-scale cutbacks as a result of the economic crisis. According to many, this would mean the end of the development of Rotterdam as a film city. And yet film can play a crucial role in the current image of the city. Both the aforementioned negative vision of the future and the role of film in the development of the image of Rotterdam form the reason for starting this research.

1.3 The cinematic city

Media construct an image of the city and have a great influence on how the appearance of the city is perceived. The best-known examples of cities whose cityscape is largely conveyed by film are New York and Los Angeles. But cities such as Hong Kong and Tokyo also owe their image to the local film industry. The appearance of these cities is etched on our retinas thanks to film, even if we have never been there. Jean Baudrillard describes this feeling in America (1988) as follows: 'The American city seems to have stepped right out of the movies. […] [The] feeling you get when you step out of an Italian or a Dutch gallery into a city that seems the very reflection of the paintings you have just seen, as if the city had come out of the paintings and not the other way around' (p. 56). In this way, walking through the streets of New York, for example, you can get the feeling of being on a film set.

Despite the fact that the city plays a major role in many films, film studies have paid little attention to this phenomenon for a long time. While city and art historians have made many contributions to the field of visual representations of the city in paintings (Arscott et al., 1988; Clark, 1984; Daniels, 1986; Olsen, 1983; Pollock, 1984; Shapiro, 1984) and photography (Batchen, 1991; Tagg, 1988, 1990). It was only since the 1990s that film scholars have increasingly focused on the concept of the cinematic city. They began to investigate how film reflects social and economic developments in cities. In other words, how film constructs an image of the city. David B. Clarke is one of the authors who has studied the relationship between film and the city. Clarke states in the introduction to the collection The Cinematic City (1997): 'the city has undeniably been shaped by the cinematic form, just as cinema owes much of its nature to the historical development of the city' (p. 2). According to Clarke, urban development and film are inextricably linked. Without the city, film could not have developed further and films in turn have shaped the city.

1.4 Problem statement

Floris Paalman, a researcher at the Department of Media Studies at the University of Amsterdam, has already applied the concept of the cinematic city to Rotterdam. In his dissertation Cinematic Rotterdam: the times and tides of a modern city (2010), Paalman takes Rotterdam as a case study and shows how the identity of the city has been captured by film. He is interested in the socio-cultural networks that brought about the film productions and how film was used to promote modernity. Cinematic Rotterdam investigates how cinema has fulfilled a social role on the one hand and has contributed to urban development on the other. Paalman describes the film history of Rotterdam using avant-garde films, industrial films, construction films and productions commissioned by the municipality, such as educational and promotional films. He argues that the films served to promote modernity. The films have contributed to the formation of the image of Rotterdam. In my opinion, it is not the individual films that influence the image of the city, but the film genre to which the film belongs. Contemporary film productions, whether short films, feature films, television series or commercials, construct an image of Rotterdam that is dependent on genre conventions.

In addition to Paalman's work, this thesis will use film genre theory as a guideline and argue that not only does the individual film determine the image of Rotterdam, but that the genre to which the film belongs constructs the image of the city. Using recent cinematic works, I will investigate how the various genres use the city as a backdrop. And how has all this contributed to the image of Rotterdam? These sub-questions lead to the research question: To what extent is the image of Rotterdam determined by films by the film genre to which they belong?

1.5 Build-up

First, in Chapter 2 The development of the image of Rotterdam, based on studies by Van de Laar, an explanation of the economic and urban development of the city will be given. This development will be divided into different time blocks that are related to the prevailing image of the period in question. Linked to this, I will use films by Andor von Barsy and Joris Ivens, but also two documentaries by Jan Schaper and Dick Rijneke, to study how the films provide a representation of Rotterdam. In Chapter 3 Genre conventions and the cinematic city, a description follows of the different ways in which film genres portray the urban space. This discusses the genres city symphony, crime film and commercial film. These are three film genres that are characterised by the use of the urban environment as a backdrop. Using film genre theory, the chapter discusses the different genre conventions that influence the way in which the urban space is depicted. In the following Chapter 4 Case studies, I will investigate how the genre conventions in the films about Rotterdam construct the image of the city. As research objects, I will discuss two films from each genre. These are the two city symphonies Die Stadt, das Glück (Ruud Terhaag, 2004) and Havenblues (Marcel Visbeen, 1999), the crime films Carmen van het Noorden (Jelle Nesna, 2009) and Who am I (Jackie Chan, 1998) and the commercials Come wander with me (RVS Verzekeringen; They, 2008) and Open your eyes (Fiat, 2006). I will use genre conventions to argue with which cinematographic means the films portray the urban space of Rotterdam. Chapter 3 serves as the basis for Chapter 4 Case studies in which I will demonstrate by means of film analysis how the films from the different genres typify Rotterdam. In what ways do the genres portray this specific city and how does this correspond with the prevailing image of the city? Finally, I will give my final conclusion and recommendations.

In the running text of Chapter 4, reference is made to the Appendices for the detailed descriptions of the films. After Appendix 1 lists the credits of the discussed films, Appendix 2 contains a series of stills per film with the aim of further illustrating the film analyses. The compilations of stills give an impression of the film images that show the cityscape of Rotterdam. Finally, in Appendix 3 I have added my final paper 'The sound of the city: the characterization of the city by film sound' for the Theme Seminar Voice, Sound, Silence & Music. In this I also take Rotterdam as a case study and, using the insights of Raymond Murray Schafer's book The tuning of the world and Urban Studies, I investigate how the unique urban soundscape, or ambient sound, can be defined. The paper poses the question of whether a specific city has its own sound and whether this is also expressed in film. In addition to Havenblues and Carmen van het Noorden, I will also take Karel Doing's Images of a moving city (2001) as objects of research and will argue that the films not only construct the image of Rotterdam with images, but that sound also plays a crucial role in the formation of the typical Rotterdam soundscape.

1 THE DEVELOPMENT OF ROTTERDAM'S IMAGE

The Netherlands has no other city whose identity is so strongly determined by its energetic inhabitants. Outsiders who hardly bother to delve into the character of the world's largest port city still believe that shirts are sold there with rolled-up sleeves (Van de Laar 2000: p. 7).

In order to get a good picture of the current image of Rotterdam, it is important to map out the historical developments of the city. The history of a city determines the cityscape and thus the image of the city. City historian Paul van de Laar has studied the history of Rotterdam extensively. In Stad vanformaat (2000), Van de Laar describes how Rotterdam developed from a traditional shopping city to a transit port or transit city at the end of the nineteenth century. He also discusses the reconstruction after the bombing of 14 May 1940 up to and including the image of the cultureless working city of the 1970s. What makes Van de Laar's work indispensable for this research is that, in addition to the connection between urban development and politics and culture, he also describes the changing image of the city. In this chapter, I will use his work to provide a concise history of the development and changing image of Rotterdam from the end of the nineteenth century to the present. In addition, I will use four films; Andor von Barsy's The City That Never Rests (1928) and Hoogstraat (1929) and Joris Ivens' The Bridge (1929) and Rotterdam-Europoort (1966), and two documentaries; Jan Schaper's City Without a Heart (1966) and Hans de Ridder and Dick Rijneke's 'It's Just Not Beautiful Anymore (1976), analyse how the existing image of Rotterdam within the different time periods is represented in the films.

Van de Laar divides the history of Rotterdam of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries into four ideal types: shopping city (1813-1850); transit city (1880-1940); working city (1945-1975) and cultural city (after 1975) (p. 8). Because the image of the city has changed considerably in urban development since the 1990s as a result of a wave of high-rise buildings, I add a fifth ideal type: high-rise city (1990-present). This is also the period from which the film objects originate in the film analyses of Chapter 4.

2.1 Shopping city

In the early eighteenth century, Rotterdam was a traditional merchant city in which trade and shipping were the main sources of wealth. In the seventeenth century, the city area had expanded enormously thanks to the rapidly increasing trade and shipping activities. However, in the eighteenth century this came to an end and new developments changed the image of the city. Rotterdam began to play an increasingly important role as a competitor to Amsterdam and other Northern European and Italian merchant cities. The merchant city experienced great economic progress and this was reflected in the cityscape. There was a strong relationship between the wealth of the elite and spatial planning. For example, the orientation towards the river became very important; a representative waterfront was seen as the most important image of the city. [1] Because there was less emphasis on the turbulent growth of the port area and the city, the wealthy port barons built stately homes. The municipality, institutions such as the VOC and religious institutions built a large number of monumental buildings. 'Many observers ignored the declining economic activity and were mainly 'enchanted' by the activity and the beautiful new buildings' (Van de Laar, Van Jaarsveld 2004: p. 26).

In Stad in aanwas (1999), Arie van der Schoor describes that until the mid-nineteenth century, visitors to Rotterdam were repeatedly impressed by the monumental riverfront with the Boompjes as the main eye-catcher. At that time, the city was seen as a small but pleasant shopping city. Historian Jacob Kortebrand confirms this image in his description of the city in which he glorifies Rotterdam: 'and if one notices the fresh air and the twice-daily refreshment of fresh water that one has in the city, and in addition the pleasantness of the trees that have been planted along all the harbours, without exception, as well as so many magnificent buildings that one finds throughout almost the entire city, one will be forced to conclude that this city does not have to yield in pleasantness to any other city in Holland' (ibid.: p. 27). But in the mid-nineteenth century a new development arose in the harbour, namely the rise of transit traffic, or the transhipment of goods. This development had major consequences for the appearance of the city and its port.

2.2 Transit city

The transformation from a commercial city to a transit city did not happen overnight. Despite the economic changes, in which Rotterdam played an increasingly important role in the transport of goods to and from the German hinterland and England, the city still saw itself as a commercial city in the mid-nineteenth century and not as a budding world port. [2] Van de Laar notes that Rotterdam had not let go of the image of a commercial city in the period 1850-1880 in a mental-cultural sense and therefore did not yet see itself as a transit city. This is due to the merchant traditions that largely determined the cultural climate of the city. Around 1880, Rotterdam began to focus more on transit traffic, with the result that the port infrastructure had to be adapted to the new logistical function. Transit ports were built to process the thousands of tons of coal and ore that came down the Rhine in ships. In addition, the construction of Pieter Caland's Nieuwe Waterweg (1872) was completed, creating a direct open connection between the ports and the North Sea. In addition, existing ports were improved for the most modern ships and a new railway network was constructed. Thanks to these large-scale investments, Rotterdam grew in the period 1880-1914 to become the most important port in Europe and a major player in the competition with other world ports.

Major infrastructural changes led to a boom in industry and turned Rotterdam into an industrial city on the river. Within the circles of the Rotterdam Chamber of Commerce, the transition to Rotterdam as a transit city was experienced as a clear mental break with the past. The image of the beautiful, representative shopping city made way for the transitopolis. Rotterdam became a busy and materialistic industrial city in which the cityscape of the once small-scale Dutch shopping city was determined by harbour cranes, large freight ships and high chimneys that produced thick plumes of black smoke. Rotterdam journalist Henri Dekking describes the image of the city at that time:

The fairly general opinion imagines Rotterdam as a brazen parvenu, riding high on his stupid luck, made rich by happy speculation and now feeling too high for the conversation to which he actually belonged. A city in its inclinations and opinions annoyingly materialistic, living in business, its whole existence an orgy of making money. [3]

The rapid growth of the port area led to a huge increase in employment. Workers came to Rotterdam from all over the world to work. The newcomers were housed in cheap housing on the left bank of the Meuse, which was soon called the farmers' side. Rotterdam became a migrant city and was one of the fastest growing cities in the Netherlands. Around the turn of the century, the total population consisted of three hundred thousand inhabitants and major expansion plans had to be made to accommodate the flow of migrants. Van de Laar states that Rotterdam was seen as the transit city where migrants moved to work in the ports. 'At that time, the migrant city was even compared to a booming American city, where immigration and lack of culture seemed to go hand in hand' (p. 10). The city's image deteriorated, but most Rotterdammers paid little attention to this. The Rotterdam city council even used the image of the transit city to justify its one-sided port and traffic policy (ibid.). Van de Laar adds that transit city Rotterdam did not have to pay as much attention to its appearance and cultural achievements, because people from outside Rotterdam valued the city differently than, for example, The Hague or Amsterdam (ibid.). Nevertheless, the city council began to worry about the negative image of the acultural city. As a result, subsidies for commercial theatre and other 'offensive' culture were stopped and these were replaced by alternative forms of culture that were too expensive for dock workers. The entertainment was not distinctive compared to other cities and the cultural life in the city declined sharply. These interventions to improve the city's image on a cultural level therefore had little effect.

On the eve of the First World War, the transit city was seen 'as a port city that, blinded by tonnage, had neglected its appearance and culture and thus lost its urban character; as if Rotterdam had forfeited its city rights' (Ibid.: p. 393). The once vibrant, beautiful shopping city had made way for the transit city in which every aspect of urban life was absent. Resistance arose against materialism, partly as a result of the crisis caused by the collapse of the German hinterland after 1918. This made Rotterdam aware of the disadvantages of its one-sided economic policy. People wanted to make the city less dependent on the hinterland and, in addition to a more versatile economic structure, also compete with other cities in cultural and urban development terms.

Until the 1940s, Rotterdam changed into a city of traffic. Due to the increasing traffic density, numerous traffic plans were developed to improve the flow. A system of main and secondary roads had to be constructed. A central figure was Willem Gerrit Witteveen, who presented the design of the framework of Greater Rotterdam. A new Rotterdam had to be worked on. Traffic breakthroughs were realized through the old city districts and the old canals and large parts of the river Rotte were filled in. The filled-in Coolsingel changed into a representative city boulevard and formed the new administrative and commercial center of the city. Modern architects built a new city hall, a post office and the stock exchange building. Architect Willem Dudok built the prestigious department store De Bijenkorf (1930). The Schiedamsedijk was known for its vibrant nightlife and the city has a high density of cinemas where films are the first to premiere in the Netherlands.

Despite the increasing traffic, Rotterdam was a dynamic, internationally oriented city in the days before the Second World War. This forms a stark contrast with the much more negative image of the city around the First World War (Van de Laar, 1998a). This is also evident from the work of the critical LJCJ van Ravesteyn: 'And the new Rotterdam is now growing into unity, has already let go of the idea of a mere working city, with residential accommodation as a necessary appendage of the port, businesslike and down-to-earth; of the port whose equipment had long since acquired a world-wide reputation. A new Rotterdam is growing in which both parts, city and port, are equal' (1948: p. 7). The city had become aware of the image of a cultureless working city and did everything it could to restore this negative image. For example, Ben Stroman writes: 'Rotterdam has been scorned for so long as a dirty, cultureless drudge that it has been deeply shocked by it while working' (De Maastunnel 1938: p. 123-125). There was a so-called New Psyche of Rotterdam that was supposed to give the city a new identity, a city in which external beauty would be preserved and spiritual life enriched.

In the 1920s, Rotterdam was the most modern city in the Netherlands. The city government wanted to promote the city in order to convey and promote modernity. One means that was used was the city promotion film. The films had to promote the modernity of the port city and served as an attractive billboard for investors from outside. But filmmakers were also inspired by the latest techniques that were applied in the port and life in the modern city. The following two paragraphs are devoted to three films that on the one hand represent Rotterdam at that time and on the other hand provide a vision of the existing image of the city.

2.2.1 The City That Never Rests and The Bridge

In 1928, Hungarian cameraman and photographer Andor von Barsy made one of the most remarkable films that had Rotterdam as its subject: The city that never rests. The fifty-minute city symphony was inspired by the popular Berlin, die Sinfonie der Grossstadt (Walter Ruttman, 1927). The city that never rests was initially intended to promote modernity and is announced with: 'Rotterdam now in the century of fast traffic'. The film focuses on the mobility and movements of life in the big city and the activities in the port. We see images of the busy traffic in the city centre, infrastructural works such as Waalhaven airport, the Maas bridges and railway lines, shipping traffic and freight transhipment in the transit ports. The city that never rests paints a positive picture of the city, the port and its inhabitants. Although three quarters of the film images show the port activities, Von Barsy also gives a more nuanced picture of the city centre. On the one hand, the grandeur and modernity of the city are celebrated, but on the other hand, the characteristics of the old commercial city are not left unexposed. With this observation I want to show that Rotterdam in the 1920s was liked as both a historical commercial city and a modern transit city. By means of moving and (extremely) high camera angles, moving objects in every shot, Von Barsy portrays Rotterdam as a grand, hypermodern and dynamic city.

First of all, the film shows all kinds of mobility in the city and the harbor within a dynamic compilation of shots. Von Barsy films the traffic in the streets and on the bridges: we see, besides the pedestrians, horse and carriages and cyclists, mainly cars and trams. The city centre is bustling with life, dominated by the movements of modern means of transport. The tram network in particular, which had no fewer than twenty-five lines around 1930, appears in a large number of shots (image 1). In addition, we see all kinds of ships sailing through the canals, channels, harbours and the river. Von Barsy captures the road and water traffic in such a way that it seems as if the city is constantly moving. Thanks to a mobile camera position, usually from a moving cart, car or ship, the dynamics of the street scene are enhanced. A high camera position is also regularly taken to make an overall shot of the traffic flows. This creates the idea of a city that is constantly moving. But Von Barsy also makes the camera the subject, so that the viewer moves into a character who is observing the city. It is as if the viewer is visiting the city.

Image 1: shots of the busy traffic on the Maas bridges and in the city center. Andor von Barsy. The city that never rests.

Secondly, Von Barsy uses the same cinematographic means to emphasise the grandeur of the city and the harbour. The filmmaker shows the busy shopping streets, the grand boulevard of the Coolsingel by means of a high angle shot filmed from a tall building (figures 2 and 3). The harbour areas are also filmed from a bird's-eye perspective, usually with an overall shot from an aeroplane or from large harbour cranes. In addition to the traffic, high-rise buildings are also a characteristic of the big city. Van Ulzen notes that Von Barsy's The White House, for a time the tallest office building in Europe, is filmed without the top, 'so that the suggestion is created of a skyscraper that climbs much further into the sky out of frame' (p. 58).

Image 2 and 3: aerial shots showing the grandeur of the Coolsingel boulevard with the city hall and post office. Andor von Barsy. The city that never rests.

The most remarkable camera angle is taken by Von Barsy from the movable part of the lifting bridge, the Koningsbrug (also called the Hef). The shot shows the city from a great height, with the shot being framed by the steel constructions of the bridge. The bridge section then descends, causing the shot to also tilt downwards. This creates a special effect because the moving perspective of the view of the city is set in motion by the movement of the technology. Because the moving bridge becomes the object and looks down on the city as it descends, Von Barsy illuminates the city from a new perspective, a perspective made possible by the arrival of the modern technical structure. Von Barsy's extreme camera angles express modernity on the one hand, and the large scale of the city and the port on the other. Rotterdam is portrayed as a large metropolis like Berlin or Paris.

The modernity and large scale are accentuated by subtitles: 'With regard to the technical equipment for the transhipment of bulk goods such as ore, coal, grain, wood and petroleum, Rotterdam is one of the most important ports in the world'; and: 'The Waalhaven is the largest artificially constructed port in the world'. But the grand plans for the future are also made known: 'In the near future, new, even larger port plans will be realised, and the peaceful appearance of arable land and pasture will soon be replaced by the imposing image that the modern world port offers'. The film presents the port of Rotterdam as one of the most modern in the world and also looks forward to a glorious future.

By far the most famous film that pays tribute to Rotterdam architecture during this period is the avant-garde montage documentary De brug (1928) by Joris Ivens. Like Von Barsy, Ivens takes the Hef, which opened at the end of 1927 and was the first lifting bridge in Western Europe, as his subject and thanks to his film the bridge enjoyed international fame. The images show trains passing the bridge, the raising of the middle section of the bridge, a train that stops, ships passing by and the train continuing its journey. Like De stad die nooit rust (The city that never rests), De brug is a film about movements within urban space. Paalman states: 'These various movements provide abstract imagery, visual patterns, dynamic compositions and contrasting views. Through the film's expressive editing the different perspectives interchange and create a rhythm' (p. 51). Like Von Barsy, Ivens was inspired by the movements and the functioning of the new bridge. But where Von Barsy mainly makes a functional film, Ivens has more eye for the aesthetics of the technique. Both filmmakers are mainly interested in the movement of the up and down bridge section, which plays a prominent role in the films. The Bridge, like The City That Never Rests, shows the most modern techniques that Rotterdam has to offer. Thanks to the influence of Von Barsy and Ivens, Rotterdam was portrayed as a modern port city in the image of the 1920s and was also seen as such. Rotterdam wanted to use film to convey this image to the outside world, in order to justify the one-sided policy that was focused on the port. But The City That Never Rests also shows another side of the city.

Although The City That Never Rests and The Bridge emphasize the movements of Rotterdam as an industrial port city, The City That Never Rests also shows another side of Rotterdam: namely the pleasant aspects of life in the city and the ports. In The City That Never Rests, images of pleasant shopping streets, busy thoroughfares, over bridges and through the canals and channels are alternated in quick succession. We see stately buildings, green lanes, characteristic facades and old ships in the ports and canals of Delfshaven, the Oude Haven and the Delfse Vaart (image 4). In addition, the tranquility in the park and the garden village of Heijplaat is highlighted. Von Barsy therefore not only shows the most modern aspects of the city, but also discusses the characteristic elements of the beautiful shopping city that still determine the street scene in that period. In contrast to the previously mentioned busy traffic flows, the film also shows the quiet areas of the city. The rustic parks, old neighborhoods and ports where time seems to stand still. In Von Barsy's second film about Rotterdam, Hoogstraat (1929), he also shows the other side of the large transit city.

Image 4: The historical facades of Delfshaven. Andor von Barsy. The city that never rests.

2.2.2 High Street

Von Barsy made Hoogstraat a year after The City That Never Rests and, like The Bridge, is a more avant-garde representation of the city. Paalman describes the essence of Hoogstraat as follows:

The film begins and ends with a small puppet theater, as a welcome and good-bey to the show. Hoogstraat is a show about showing: the show cases of the shops, performers giving shows, the people in the street showing themselves, which all together make up the show of the city. The glass window is central to the film. It is a medium itself, because of its function of exhibition, its framing, transparency, reflections and its effect of double images and visual layers (Paalman, 2010: p. 109).

In Hoogstraat too, the camera is the subject of the film and '[observes] the diversity of people and the way they behave' (Ibid.). The film is an aesthetic representation of the urban space and the people who move in it. The images show a busy but pleasant shopping street, where passers-by from all walks of life stroll past the shop windows (image 5). It is clear that this expressive representation of Rotterdam does not highlight the mechanical aspects of the city, but focuses more on the human aspect. In Hoogstraat, Von Barsy pays tribute to life in the modern city, which is characterised by the latest form of pastime, namely consuming.

Image 5: shot showing shoppers from a shop window. Andor von Barsy. Hoogstraat.

In short, The City That Never Rests is an ode to the latest technological means of port and industry and also shows Rotterdam as a large modern world city like Paris, London and Berlin. But Von Barsy also explicitly highlights the characteristics of the old commercial city that still characterize the city center in the 1920s. The image of tonnage in the materialistic transit city is on the one hand glorified by the films of Von Barsy and Ivens because they accentuate the beauty of the dynamic port city. On the other hand, the films also show the pleasant aspects of the city that actually refute the negative image.

2.3 Working city

The Second World War literally broke the historical development of Rotterdam. The city's image was transformed from a transit city to a working city. On 14 May 1940, the Germans bombed Rotterdam as part of the German attack on the Netherlands. Almost the entire historical city centre was destroyed by the bombing, but also by the fierce fires that raged for several days. The city centre was transformed into a smoldering heap of rubble, in which 24,000 homes were destroyed, 800 people were killed and 80,000 people were left homeless. Miraculously, the city hall, the post office, the Beurs, the Laurenskerk and a number of other buildings were largely spared. Van de Laar states that Rotterdammers saw the destruction of the city centre as a clear break with the past. During the reconstruction period, it therefore seemed as if they wanted to rewrite history (p. 398).

The city centre was rebuilt according to the Van Traa Basic Plan. The plan, which was nothing more than a zoning plan, served as a blueprint for a prosperous city that formed a great contrast with the pre-war city. The Basic Plan was limited to four urban functions: traffic, work, living and recreation; and kept these functions strictly separated. The centre was designed according to a grid of inner and outer roads in a strict interplay of lines of through and connecting roads. Van Traa saw the spared buildings as a hindrance to modern urban development. Many damaged buildings were not repaired, but demolished, including Dudok's Bijenkorf. Nevertheless, the people of Rotterdam managed to prevent the demolition of a number of historical buildings. The city was given a modern appearance that radiated businesslike and functionality. This fitted in with the idea of the modernist movement.

Rotterdam had to take its own independent place compared to Amsterdam and The Hague. Where the capital and the court city are cities of the past, Rotterdam had to become the modern city of the future (Van de Laar 2000: p. 463):

One can see Rotterdam in the year 2000 as the great, modern social city of the Netherlands; one can see Rotterdam as the city that is the welcome addition to our national life of the two other cities: Amsterdam and The Hague; Amsterdam the great, old, historical cultural city, The Hague the administrative centre, Rotterdam the great, modern social centre (Handelingen 1946: p. 137).

The reconstruction programme was ambitious both in terms of urban development and in the development of port industrialisation. As a result, other social and cultural functions were subordinated for a long time. In the period 1945-1970, Rotterdam was profiled as the 'no words, but deeds' city. As a result of the construction of new residential areas that were set up according to the so-called neighbourhood idea, the people of Rotterdam only came to the city centre to work. According to Van de Laar, the city centre was still seen as the pre-war transit city. But now Rotterdam had become a functional city that was boring, cold and uninviting. Rotterdam became a city that represented the material and immaterial content of the working city in image and form. The new Rotterdam also had to become a beautiful working city again. According to Van de Laar, this was expressed in the image of the relationship between Rotterdam and its river. However, the city as a window on the river became one of the great failures of the plan (p. 463).

During the Second World War, some hoped that the reconstruction city would start with a clean slate: a city with a different look and a new cultural face. After 1945, however, Rotterdam did not succeed in shaking off the one-sided image of the working city; moreover, people did not want to. The image of the working city fitted in very well with a policy in which the business community, the Chamber of Commerce, politicians and civil servants jointly led the implementation of the reconstruction programme (ibid.).

Van de Laar states that Rotterdam created a modernist image of itself during the reconstruction; an image that was based on the few examples of internationally appealing architecture in the city (p. 480). Many large department stores were built, which received much appreciation from urban planners and strengthened the image of Rotterdam as a modern reconstruction city. Rotterdam acquired the image of a working city and strove to develop into a model of modernity. In 1953, the construction of the Lijnbaan (Van den Broek and Bakema) was completed as the first car-free shopping street in Europe and received much international praise. A new Central Station was also built (1957) and the Groothandelsgebouw (HA Maaskant and W. Van Tijen, 1953) was built right next to it. In 1960, the Euromast (HA Maaskant and JP van Eesteren) was festively opened on the occasion of the Floriade and since then, together with the famous statue De Verwoeste Stad (The Destroyed City) by Ossip Zadkine, it has formed the symbol of post-war Rotterdam. Rotterdam is the first city in the Netherlands to have a metro, which opens in 1968 and connects both banks of the Maas. Despite the positive reporting about the city, most Rotterdammers were less concerned with the new cityscape (ibid.: p. 481). Van de Laar also sees that Rotterdam is the city during the reconstruction period where 'No words, but deeds' was elevated to a kind of religion (p. 481). Nevertheless, there was dissatisfaction about the result of the reconstruction. The human aspect of the city in particular was said to have been pushed into the background. Joris Ivens has depicted the alienation of man in the new Rotterdam well in Europoort-Rotterdam (1966).

2.3.1 Ivens' Rotterdam Europoort

Rotterdam-Europoort is a promotional film for the port, but also shows the result of the reconstruction and mixes fact with fiction by adding a modern interpretation of The Flying Dutchman. Like Andor von Barsy, Ivens shows the image of modern Rotterdam in the context of the information film, but then from after the Second World War. Despite the fact that the film is intended as a promotional film, Ivens makes some critical remarks about the port city.

The film reflects upon the interconnection between port and city. It results in an alienating interchange between images of pilot boats and youths riding mopeds, people coming out of a cinema and warehouses, movements of ships and people at the railway station. This alienation is reinforced by a collection of futuristic images throughout the film, which is further reinforced by Tom Tholen's sometimes abstract sound score that turns this film into 'reality science-fiction'. This applies particularly to aerial shots of the petrochemical industry. [...] Rotterdam-Europoort shows an oscillation between political divides, city and port, art and industry, reality and fiction. (Paalman: p. 285).

Rotterdam-Europoort uses images and sound to sketch a futuristic character of the city and the port. The aerial shots of the petroleum industry of Pernis are aesthetic in nature on the one hand, but on the other hand the shots refer to an imaginary city of the future. The images show chimneys, burning torches, oil refinery installations, all richly lit and against a twilight background (image 6). The industry is depicted as an ominous landscape. In addition, alienation in relation to man is created by the shots in which aerial shots of the bombed city are followed by a lonely individual amidst gigantic oil storage tanks. The landscape has been transformed by the post-war developments in such a way that man has become alienated from his environment, as is often the case in modern cities. For example, Ivens states about his film in an interview:

I believe that it is my best film, I'm happy with it. It is good, strong, has a vigorous style and is new in its form of expression. It has become much more concise than I expected, giving the city and the harbor relief that is necessary in a film of these days. // One could say that is is a tribute to Rotterdam, the power of its harbor and the city are in it – of course also things like depersonalization and uniformity (...), which Rotterdam has in common with every modern city (Quote from Ivens, quoted from Paalman: p. 286).

The underlying layer of Rotterdam-Europoort criticizes the one-sided reconstruction program that focuses on the expansion of the port, industry and commerce. As a result, the population has become alienated from the city. Although the film was intended to promote the port, the images show a doomsday scenario for the inhabitants of Rotterdam. In this example, the film gives a critical impression of the prevailing image of the resurrected Rotterdam of the 1960s. Ivens, like Von Barsy, sees the city as a modern world city that experiences the same problems as other world cities.

Image 6: Aerial shot of oil refineries as a futuristic landscape in Rotterdam-Europoort. Joris Ivens. Rotterdam-Europoort.

2.4 City of Culture

Until the 1970s, the port area had expanded considerably: with the Botlek area, the Europoort and, as a highlight, the construction of the Maasvlakte. As a result of the enormous port expansion, Rotterdam was allowed to call itself the largest port in the world in 1962. However, the oil crisis of 1973 put an end to the industrial era and the unbridled growth of the oil and petrochemical industry until then. The post-industrial period that followed brought new developments in the logistics network, which meant that the port of Rotterdam entered a new phase. [4] Just as in the years before the war, the economic crisis led to a rethinking of the future of the port city. The city continued to grow unabated and, due to the housing shortage, a number of apartment districts were built at a rapid pace; Hoogvliet, Pendrecht, Zuidwijk, Lombardijen, Ommoord and Zevenkamp. Residents protested against the dominant and highly polluting industrial ports, but also against the increasing traffic pressure on the city centre.

Within a short period of time, the population composition of the old city districts, whose houses no longer met the requirements of that time, changed. The middle class left for the peripheral municipalities and guest workers from Spain, Italy, Turkey, Morocco, Cape Verde, Suriname and the Netherlands Antilles came in their place. Rotterdam changed into a multicultural society, the social underclass of which was mainly formed by immigrants. Riots regularly broke out between different population groups and the poorly maintained nineteenth-century houses became dilapidated. In addition, the drug problem grew and the city was confronted with a high percentage of drug addicts at the end of the 1970s.

The period of the 1970s is also characterised by the many bare spots in the city that still had to be built. The local population increasingly found the city uninviting and cold because of the many grey concrete facades and wide roads. The working city also had a bad name in terms of going out: the pre-war bustling centre had not returned and was deserted in the evenings. From the second half of the 1980s, Rotterdam made an attempt to bring its urbanity and cultural appearance into line with its economic significance. The municipal government emphasised the development of an attractive residential city, social innovations and an attractive cityscape. A new political climate ensured that the city centre was revived. Large-scale urban renewal took place and the importance of improving the cultural climate was placed above the expansion of the port. In the context of the so-called C70 manifestation, the city centre was thoroughly tackled. Car traffic was kept out as much as possible and new homes were built in the form of high-rise buildings, as an expression of the metropolitan residential function. In addition, the city council is trying to make the cold city centre more pleasant. They are doing this by redeveloping the Coolsingel, among other things. But also by building more compact new buildings, such as the cube houses by Piet Blom, the red pointed roofs of the complex by Jan Verhoeven and the entertainment area of the Oude Haven. The effect of the concept of the so-called 'compact city' was that the new city districts acquired a village character. Rotterdam received an unprecedented cultural boost. For example, the city got a new municipal library, a new Maritime Museum, an extension of the Museum of Ethnology and the Historical Museum Rotterdam settled in the restored Schielandhuis.

2.4.1 City without a heart and it's just not beautiful anymore

The renewal of the city centre was the result of large-scale protests by the Rotterdam population, as is also evident from various documentaries about the city. Van Ulzen takes the documentary Stad zonder hart (1966) by Jan Schaper as an example, and compares the film with De stad die nooit rust (The city that never rests). She notes that where in Von Barsy's De stad die nooit rust traffic and high-rise buildings are seen as something positive, Stad zonder hart approaches these elements from a negative perspective: 'his aim is to show how quickly the city centre empties every evening between half past five and half past six and is left completely deserted'. The commentary on the images of a deserted Rotterdam reads: 'austere facades, which evoke a cold, defensive mood' (Van Ulzen 2007: p. 66). But also:

And whoever sees the lights of the thousands of cars, and then turns his eyes to the city, which has just turned on its lights, thinks: Rotterdam is a world city. But whoever arrives in the centre an hour later, sees the magnificent fountain and the large buildings of the concerns, and he hears the beautiful carillon, but he finds the Coolsingel and the Raadhuisplein empty, or at least, he encounters almost no people there (Ibid.: p. 65).

According to Van Ulzen, the lifeless city centre is the negative consequence of the one-sided urban planning in which in the city centre, where previously 25,000 houses with 100,000 Rotterdammers stood, 5,000 homes and the rest offices, banks, insurance companies and wide roads (p. 66). Images of the pre-war busy and pleasant Rotterdam are juxtaposed with the images of the empty streets of the new Rotterdam.

In addition to the unpleasantness of the modern city centre, the film also criticises the deterioration of the old neighbourhoods. The documentary 'T is gewoon niet mooi meer (1976) by Hans de Ridder and Dick Rijneke shows the impoverishment of the old city neighbourhoods, accompanied by critical commentary from residents. The documentary criticises the one-sided reconstruction programme of the city centre, in which the emphasis was on the development of offices and banks, because according to the commentary of the residents 'the most money could be made from that'. Images of old facades alternate with images of modern office buildings. In 'T is gewoon niet mooi meer' the sterile, modern city centre is also compared to the old Rotterdam. For example, it is stated that the Coolsingel was a series of catering establishments, where you could only shuffle past because of the crowds. The austere architecture of the city centre also stands in stark contrast to the neglected houses. 'T is gewoon niet mooi meer shows the traffic congestion, the stench of factories and the arrival of bars and sex clubs where shops used to be. In the second half of the documentary, the new plans are presented to renovate the neighborhoods and build affordable new construction. Both films form a remarkable representation of the dissatisfaction that prevailed about the liveability of Rotterdam and also confirm the image of the city in the period of the '70s.

2.5 High-rise city

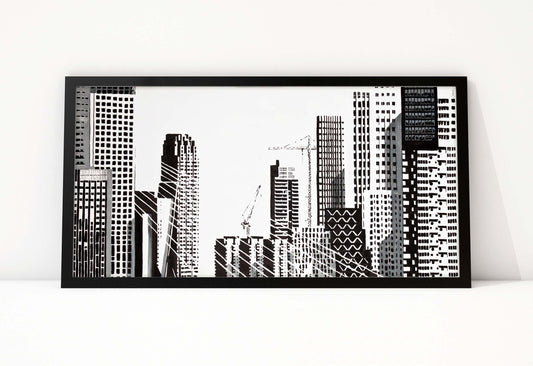

In the 1990s, the desire to get rid of the bare, cold image started again, but it was slow going. The city wanted to attract more residents to the city centre and focused on a large number of high-rise projects. Up until the 1990s, the development of high-rise buildings was opposed as much as possible by the left-wing city council. For example, the Shell building on the Hofplein was labelled at the time by Hans Mentink (Labour Party) as 'an erection of capital'. And this while the White House was the first skyscraper dating back to 1897. But as the reconstruction progressed, high-rise buildings in the city centre became increasingly common from the 1980s onwards. Rotterdam was looking for a new image and high-rise buildings fitted in with that. Where previously no buildings were allowed to be built higher than the Hilton, a high-rise cluster arose on the Weena, including the Nationale Nederlanden office building (150 metres), which had the appearance of a representative and international office boulevard. 'Rotterdam was a port city, but at the same time eagerly looking for companies that matched the glamour of “global economy”' (Van de Laar, Van Jaarsveld 2004: p. 76). Also on the southern bank of the river, investments were made in new residential and working areas from 1994 onwards. The old port areas in the city centre, which were constructed for transit traffic at the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth century, were given a new function. In the early 1980s, the plan was chosen to redevelop and maintain the form and structure of the old ports. The Kop van Zuid and Katendrecht were the first to be considered and were given a new function in which residential, working and recreational facilities were developed. The plans fitted in with Rotterdam's efforts to strengthen the relationship between city and river and to express the connection with the port in the cityscape. The area was connected to the city centre with the epitome of cultural élan: the Erasmus Bridge (1996).

Since the 1990s, Rotterdam has presented itself as Manhattan on the Maas. Although the high-rise buildings are not special compared to those in large world cities, Rotterdam is seen as the high-rise city of the Netherlands and derives its modern image from this (Ibid.: p. 76). Since 2000, high-rise zones have been designated in the city centre and around the river and one tower block after another has risen under a great deal of media attention. The projects have become increasingly ambitious, with the Coolsingeltoren (215 metres) and the Parkhaventoren (392 metres) as highlights. The latter was supposed to become the tallest building in Europe, but both projects proved unrealistic and were never carried out. In 2004, the plan for a new central station was ready, to serve the growing number of travellers, the High Speed Line and the RandstadRail.

In addition to the major changes in the cityscape in terms of urban development, the population composition has also changed significantly since the 1970s. Rotterdam now has more than 160 different ethnicities that also influence the appearance of the city. The arrival of the minarets of the Mevlana Mosque met with much criticism from Rotterdam residents, who argued that the towers are a confirmation of the failed integration policy. In 2010, the Essalam Mosque was put into use and with its 50-metre high minarets it is the highest mosque in Europe. The addition of the minarets to the appearance of the city represents the new socio-cultural and ethnic composition of today's Rotterdam.

In the period of the high-rise city, the new image of the city was used as a backdrop in films. As a result, the image of the city was influenced by film. The way in which Rotterdam is represented depends on the genre to which the film belongs. In the following Chapter 3, I will discuss, using genre theories, in which ways genre conventions frame urban space.

3 GENRE CONVENTIONS AND THE CINEMATIC CITY

3.1 Urban space and film genre

As I have described before, the city and film are inextricably linked. However, it depends on the film genre how the city is represented. In this chapter I will use film genres to explain the genre conventions in the use of urban space as a film setting. Subsequently, in Chapter 4, based on the genre theories described in this chapter, I will analyse a number of films to explain how the image of Rotterdam is constructed depending on the film genre.

Many film scholars argue that film has developed as urban art because it often tells its stories against the backdrop of the metropolis (Gold, Ward 1997: p. 61). By using the city as a setting, films create a dream city or a mythical city. The choice of a particular city can localize the narrative and thereby give it meaning, but the city can also be shown as an anonymous city. The urban landscape is shown to the viewer in various ways. The character can be shown as part of the urban space and can move around in it. But a cityscape can also function as a background. The city can be shown from a window frame of an interior or from a car, or in a reflection of mirrored material, such as car windows and glass facades. The scale of the urban space can be increased or decreased by means of perspective and camera position. This can be an extreme frog's perspective, which makes buildings appear larger and higher, but the city can also be shown from a bird's-eye perspective, which expresses the size of the city. But one can also choose to use a small part of the city, such as a neighborhood, as a setting. This reduces the scale of the urban space and gives a city neighborhood a village character, as in Spike Lee's Do the Right Thing (1989), which is set around a block in the New York borough of Brooklyn.

The urban space can also provide meaning through design and framing. When the character is placed in a large, open space, this can give a feeling of vastness and freedom. On the other hand, the space can make the character feel lonely or insignificant. Small spaces can radiate shelter and safety, but can also have a claustrophobic effect (Adang, Van der Pol 2010: p. 15). With a telephoto lens, buildings can be depicted as densely packed flat shapes, which can have an oppressive effect. The city itself can also be the subject of the film, as in Woody Allen's Manhattan (1979), in which the director expresses his love for his hometown. In addition, colour and light can influence the look and feel of the city. The urban setting can be depicted in bright, warm and realistic colour tones, as in New York I Love You (Fatih Akin et al., 2009), but also in dark, cold, stylised shades, as in the representation of Gotham City from the Batman films. The color tone of the image can also strongly influence the utopian or dystopian imagination of a city. The characteristics of a utopian and dystopian imagination of the city in film will be discussed later in this chapter.

Finally, the architecture of the built environment can be filmed in such a way that it conveys underlying layers of meaning. Mitchell Schwarzer examines the role of architecture in the films of Michelangelo Antonioni in 'The Consuming Landscape' from the collection Architecture and Film (2000). Antonioni studied architecture before becoming a filmmaker and is uniquely skilled at capturing the effects of the built world on film (L'avventura (The Adventure, 1960), La Notte (The Night, 1960), L'eclisse (The Eclipse, 1962), and Il deserto rosso (Red Desert, 1964)). Schwarzer argues:

[In Antonioni's films] [a]rchitecture both contributes to the events taking place among actors and acts independently with other objects in motion and in space. Architecture is protagonist and antagonist, nucleus for the slow collapse of perception into a space between the actors' lines, a visual language with a power all its own. As Frank Tomasulo has noted, for Antonioni, architecture “enunciates themes of ancient vs. modern, nature vs. culture, atheism vs. Catholicism, woman vs. man, and even socialism vs. capitalism” (p. 198).

Schwarzer adds that Antonioni uses modern architecture as a metaphor:

For Antonioni, modern architecture is menacing but precise; it is monotonous but exquisite. Modern architecture is Antonioni's grand metaphor for the turbulence, tedium, and sublimity that make up the age (p. 210).

There are a large number of film genres that are closely connected to the urban space as a cinematic space. Thrillers, action films and science fiction films are usually set against the background of the (imaginary) city. The way in which the city is shown depends on the genre to which the film belongs. There are three film genres that give a different representation of the city: the city symphony, the crime film and the commercial. The three genres depict the city in a completely unique way that is strongly dependent on genre conventions. Below is an explanation of the ways in which city symphonies, crime films and commercials depict the city.

3.2 City Symphony

The film genre that takes the city itself as its subject is the city symphony. City symphonies are avant-garde documentaries about everyday life in large world cities, such as Paris, Berlin and New York. The first city symphonies date from the 1920s in Europe and the United States. The films usually have a musical soundtrack and rarely contain dialogue. Furthermore, the films often show a strong relationship between place and time, because they compose a day from morning to evening. The films have a poetic character, are idealistic and emphasize the dynamism, speed and modernity of life in the city. The dynamism and speed are depicted by shots of traffic and pedestrians on the street. The modernity of the city is conveyed with images of modern transport networks such as trains, ships, car traffic but also modern architecture such as high-rise buildings and bridges. The visualizations of the urban space and the city dwellers aim to portray the feeling of the modern city as the ultimate product of modernity. This feeling is conveyed by means of rhythmic montage sequences based on the musical soundtrack. For example, Walther Ruttmann's Berlin: die Sinfonie der Grossstadt (Berlin: Symphony of a Big City, 1927) shows various activities such as work, traffic, sports, relaxation and nightlife in the German capital. Ruttmann's film is an ode to Berlin, the city he sees as the ideal modern European metropolis. In Alberto Cavalcanti's Rien que les heures (Nothing but the Hours, 1926) we see shopkeepers opening their shops, rich gentlemen in a café and an old woman waddling through the streets. The very first city symphony Manhattan (1921) by Paul Strand and Charles Sheeler shows Manhattan in a poetic and romanticized way, but also emphasizes modernity by emphasizing the grandeur of the city and its tall skyscrapers.

According to Scott MacDonald, in 'The City as the Country: The New York City Symphony from Rudy Burckhardt to Spike Lee' (1998), the genre of the city symphony can be seen not only as the representation of the modern metropolis, but also as the filmmaker's vision of the nation of which the city is a part. MacDonald: 'If Berlin: Symphony of a Big City reflects Germany's postwar hunger for social order, The Man with a Movie Camera reflects the new Communist Russia's excitement about the Revolution and the advent of modern industrialization, and Nothing But the Hours epitomizes the poverty, the cynical realism, and the aesthetic freedom for which France in the twenties has become famous' (p. 41). A more recent example of a city symphony is the Qatsi trilogy by Godfrey Reggio (Koyaanisqatsi (1982), Powaqqatsi (1988) and Naqoyqatsi (2002)). In the first and most famous film Koyaanisqatsi, modern life is not glorified but criticized. The word Koyaaniqatsi comes from the Hopi language and means 'life out of balance' or 'chaotic life' and with this Reggio refers to the fact that our lives are dominated by technology. According to Reggio, the city is the ultimate form of the place in which everything is determined by technology:

[T]hese films have never been about the effect of technology, of industry on people. It's been that everyone: politics, education, things of the financial structure, the nation state structure, language, the culture, religion, all of that exists within the host of technology. So it's not the effect of, it's that everything exists within [technology]. It's not that we use technology, we live technology. Technology has become as ubiquitous as the air we breathe (Reggio 2002).

City symphonies not only glorify the modernity of the city, but also express a critical vision of modern life. At the same time that the film genre of the city symphony was introduced, another genre emerged in which life in the city is central.

3.3 Crime film

During the late 1920s and 1930s, filmmakers began to take up the city as a subject, in Europe, as in Fritz Lang's Metropolis (1926), but also in American cinema, especially the gangster movie: Little Caesar (Melvyn LeRoy, 1930), The Public Enemy (William A. Wellman, 1931), and Scarface (Howard Hawks and Richard Rosson, 1932). The city in the crime genre is characterized by dark streets, dingy boarding houses and office buildings, bars, nightclubs, penthouse apartments, train stations, and luxurious mansions. Along with the tensions of violence and mystery, the urban environment is usually depicted at night, lit by dim street lamps and garish neon signs (McArthur 1972: pp. 28-29). The crime genre experienced a revival in the 1940s and early 1950s with the advent of film noir. These crime films are seen as a reflection of the pessimism and loss of idealism in the United States during the period of World War II. The city serves as the backdrop for a corrupt and claustrophobic world. Film noir associates the city with alienation, isolation, danger, moral decay and repressed sexuality. The alienation of the characters is expressed in their constant movement alone through the urban space (Mennel 2008: p. 49). The classic American film noir opens with shots of skyscrapers with illuminated windows at night, accompanied by a voice-over warning us of the darkness and danger of the city and then promising to show the darkness.

Frank Krutnik states in 'Something more than night' (In: Clarke 1997): 'The noir city is a shadow realm of crime and dislocation in which benighted individuals do battle with implacable treats and temptations' (p. 83). The setting of film noir is characterized by streets and alleys, which are mainly shown at night and in the rain. The areas form the cinematic environment for the alienated characters, chance encounters and chases (Mennel 2008: p. 50). According to Krutnik, the modern city in film noir is portrayed as a threat to the American community (p. 88). During this period, the result of the mass migration from the American countryside to the city was that in a foreseeable time more than fifty percent of the population lived in cities. The city in film noir is seen as a reaction to this demographic shift. Krutnik concludes in 'Something more than night':

The horror of the noir city is firmly tied to the pervasive indeterminacy of meaning. In the fictional universe of film noir, intangibility is both a stylistic strategy and a thematic obsession. Dark with something more than night, the noir city is a realm in which all that seemed solid melts into the shadows, and where the traumas and disjunctions experienced by individuals hint at a broader crisis of cultural seld-figuration engendered by urban America (p. 99).

The city can be depicted utopian or dystopian. When urban space is represented as the ultimate form of modernity, social order and harmony, we speak of a utopian representation of the city. But the cinematic city can also convey the negative effects of modernity and sketch a dystopian future image of the city, as in the cinematic representations of cities in Metropolis and Blade Runner (Ridley Scott, 1982) (Clarke 1997: p. 6). But Taxi Driver (Martin Scorsese, 1976) and Midnight Cowboy (John Schlesinger, 1967) also show a dystopian image of the city of New York. In films from the 1990s, the postmodern city is represented. Where New York symbolizes the modern city, Los Angeles is seen as the ultimate postmodern city. Barbara Mennel states in Cities and Cinema (2008): '[T]he setting of Los Angeles is central to the cycle because of its position between modernity and postmodernity. Los Angeles appears as an imaginary city without history, or haunted by its history as in The Big Sleep [Howard Hawks, 1946]' (p. 51).

The postmodernity of Los Angeles is best captured in Joel Schumacher's Falling Down (1993), which was quickly dubbed 'a Taxi Driver for the nineties'. Falling Down is about the journey of two men: William Foster (Michael Douglas) and Prendergast (Robert Duvall). Both are trying to get 'home', Prendergast to his paranoid wife who has forced him to retire, and Foster to his daughter who lives with his ex-wife. Elisabeth Mahoney writes about the film in 'The People in Parentheses: space under pressure in the postmodern city' (1997): 'Falling Down represents the dislocation between subject and city described by Paul Patton in his comment on the postmodern cityscape: the city here encodes absolute alienation and fragmentation and focuses particularly on a crisis of masculinity through and in the urban' (p. 174). According to Mahoney, urban space is hostile and violent, but also rudderless: '[T]he cityscape represents, contains and triggers Foster's violent journey. Los Angeles here is a site of stasis, the city is rotting; the film's opening sequence constructs public space as claustrophobic, invasive and stagnant [...] Foster has no sense of rootedness; the space of the city has been taken over by racial and/or secual “others”' (p. 174). Another example is Mathieu Kassovitz's La Haine (1995), in which he shows how the well-guarded centre of Paris is threatened by immigrants from the poor neighbourhoods on the outskirts of the city. In La Haine, the characteristic centre of Paris is not romanticised but portrayed as a place of potential conflict between immigrants and the police.

In short, the genre conventions of the crime genre present the urban space as an environment where danger is constantly lurking. A dystopian image of urban life is also often depicted through the emphasis on darkness, alienation and claustrophobia in the relationship between the character and the setting.

3.4 Commercial film

In commercials, the emphasis is on the positive aspects of life in the city. Commercials fall under the model of advertisements and consist of a message, code, channel, context, sender and receiver (Forceville, 1996: p. 69). In this case, the message is linguistic in nature, such as the name of the product or the slogan. But the message can also be conveyed by means of (film) images. In that case, the images can have a metaphorical function, they then form a pictorial metaphor (Forceville, 1996). In commercials, the channel is formed by the medium of television. Renske van Enschot in Rhetoric in advertising: 'People use a systematic processing strategy when they carefully examine all relevant information in the advertisement and think about this information in relation to other knowledge they may have about the product that is being advertised. [...] In [the] strategy, the judgment is determined by positive or negative feelings that are evoked by processing the advertisement' (p. 9-10). For example, the advertisement may be considered beautiful or ugly, attractive or unattractive.

In television commercials, the city and city life are often linked to the product being promoted. By using the aesthetic elements of a city, the images form a metaphor that adds connotations to the product. For example, the images of a specific city can visualize the feeling or experience that a product should bring about. In addition, the image of a brand is often linked to the image of a specific city. For example, think of perfume commercials that cleverly use the image of New York, such as the brand DKNY that romanticizes the streets of New York and thus links them to the feeling of the perfume. In financial products and services and technologically innovative products, the city serves as a backdrop to radiate modernity and innovation, just like in the city symphony. The commercials show the most modern architecture and create an idealistic image of the urban environment. The city is often shown as a perfect representation of reality, in which life forms a harmonious whole. In addition, the city is used to create spectacular images that make the commercial stand out.

The genres of the city symphony, crime film and commercial film all have their own way of using the urban space as a backdrop to add meanings to the narrative and the characters. The way in which a film genre frames an existing city creates a certain image of that city. In Chapter 4 follows an extensive film analysis of 2 to 3 films per genre. The descriptions serve as an argument for the proposition that the kind of image the films form of a city depends on the genre conventions.

4 CASE STUDIES

City symphonies, crime films and commercials each construct their own version of the cityscape of Rotterdam. Using the following case studies, I will argue to what extent the image formation of Rotterdam by films is determined by the film genre to which they belong. This brings forward a clear division in the general image that is sketched of the city. The film genres can give a utopian or a dystopian representation of Rotterdam in their approach to the city. But a genre can also bring forward both overarching characteristics. How the city is portrayed depends on the genre conventions in the field of cinematography and the design of the mise-en-scène.

4.1 City symphonies: Die Stadt, das Glück, Havenblues and opening Carmen van het Noorden

In this section I will explain how three city symphonies depict the urban spaces of Rotterdam. By means of which cinematographic aspects is the city depicted? How does this relate to the overarching genre of the city symphony? The city symphonies that are studied are Ruud Terhaag's neon-romantic poetic portrait of Rotterdam at night Die Stadt, das Glück (2004), the opening credits of the feature film Carmen van het Noorden (2009) by Jelle Nesna and the short music film full of harbour romance and life songs Havenblues (1999) by Marcel Visbeen.

4.1.1 The city, the happiness

Die Stadt, das Glück shows images of Rotterdam during a rainy night and emphasizes the movements, shapes and colors of city lights (appendix 2.1). The film starts with avant-garde shots of moving lights and then shows a tracking shot of a series of images of the street scene, filmed from a moving car. The viewer becomes the subject driving into the city center of Rotterdam on large empty roads and through a tunnel. The alternating out-of-focus filmed street lighting, colorful traffic lights and neon signs abstract the urban space into a spectacle of moving lights and colors. Terhaag is fascinated by the reflections of lights on the wet asphalt and the haze that occurs when a point of light is filmed from a car window misted with raindrops. In addition, we see the illuminated windows of large office buildings and residential towers. Die Stadt, das Glück focuses less on city life on the street and raises more questions about what happens behind the illuminated windows of the buildings. People are in offices, homes, cars, trams and in cafés and restaurants. A single shot shows pedestrians who are quickly crossing the street, sheltering under an umbrella. The editing follows the rhythm of the piece Die Stadt, das Glück from the Berliner Nachrichten opus 13, which has been restaged by composer Stephen Westra. For example, the movement of the lights in the tunnel is synchronized with the rhythm of the piano music and the drawbridge descends at the same time as the falling pitch of the song. Die Stadt, das Glück glorifies the peace that reigns in the city during a rainy night and thus romanticizes the city. The images are rhythmically edited and tell the story of a night in the city. The emphasis is on the dynamics of the traffic, the city lights and the movement in the passing buildings.